The Tragic Fate of the Afghan Interpreters the U.S. Left Behind

These men risked their lives for the U.S. military. Now many would like to come to America but are stranded — and in danger

Sakhidad Afghan was 19 when he started working as an interpreter for the U.S. military in Afghanistan, in 2009. His father was sick and he wanted to help support their extended family of 18. In his first year, he saw combat with the Marines in the Battle of Marjah, but he remained an interpreter until the fall of 2014, when American troops drew down and his job disappeared. By then he’d received an anonymous death threat over the phone, so he’d applied for a special visa to live in the United States. He’d been in the application pipeline for three years when, in March 2015, he went to see about a new interpreting job in Helmand.

Days later, one of his brothers got a phone call from a cousin, asking him to come over and look at a picture that had been posted on Facebook. The picture was of Sakhidad; he had been tortured and killed and left by the side of the road. He was 24. A letter bearing the Taliban flag was found stuffed into a pants pocket. It warned that three of his brothers, who also worked for coalition forces, were in for the same.

Sakhidad Afghan’s death reflects an overlooked legacy of America’s longest, and ongoing, war: the threat to Afghans who served the U.S. mission there. In 2014, the International Refugee Assistance Project, a nonprofit based in New York City, estimated that an Afghan interpreter was being killed every 36 hours.

The visa that Sakhidad Afghan was waiting for was intended as a lifeline for interpreters who are threatened. Congress approved the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program in 2009, and some 9,200 Afghans have received an SIV, along with 17,000 of their dependents. But the number of visas has lagged behind the demand, as has the pace at which the State Department awarded them. By law, an application is supposed to be processed within nine months; it often takes years. And now, unless Congress extends the program, it will close to applicants at the end of this year. An estimated 10,000 interpreters may be left vulnerable—a prospect that the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. John W. Nicholson, warned could “bolster the propaganda of our enemies.”

The United States has a history of modifying immigration laws to take in foreigners who aided its overseas aims and came to grief for it—a few thousand nationalist Chinese after the 1949 Communist takeover of China, 40,000 anti-communist Hungarians after the failed rebellion against Soviet dominance in 1956, some 130,000 South Vietnamese in the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War in 1975. An SIV program for Iraqi interpreters, closed to applicants in 2014, has delivered about 17,300 visas.

But Congress has been unwilling this year to renew or expand the Afghan program, for a variety of reasons. Lawmakers have taken issue with the potential cost (an estimated $446 million over ten years for adding 4,000 visas). They have questioned why so many visas had yet to be issued. Some have registered concern over the number of immigrants coming into the United States and argued that a terrorist posing as an interpreter could slip into the country.

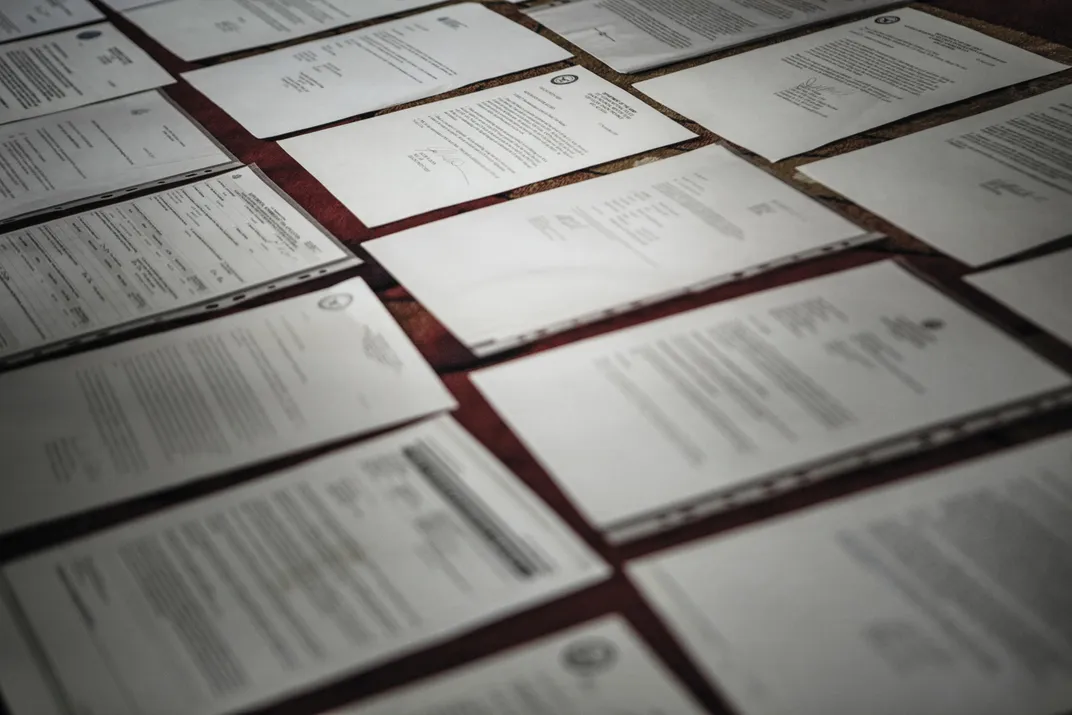

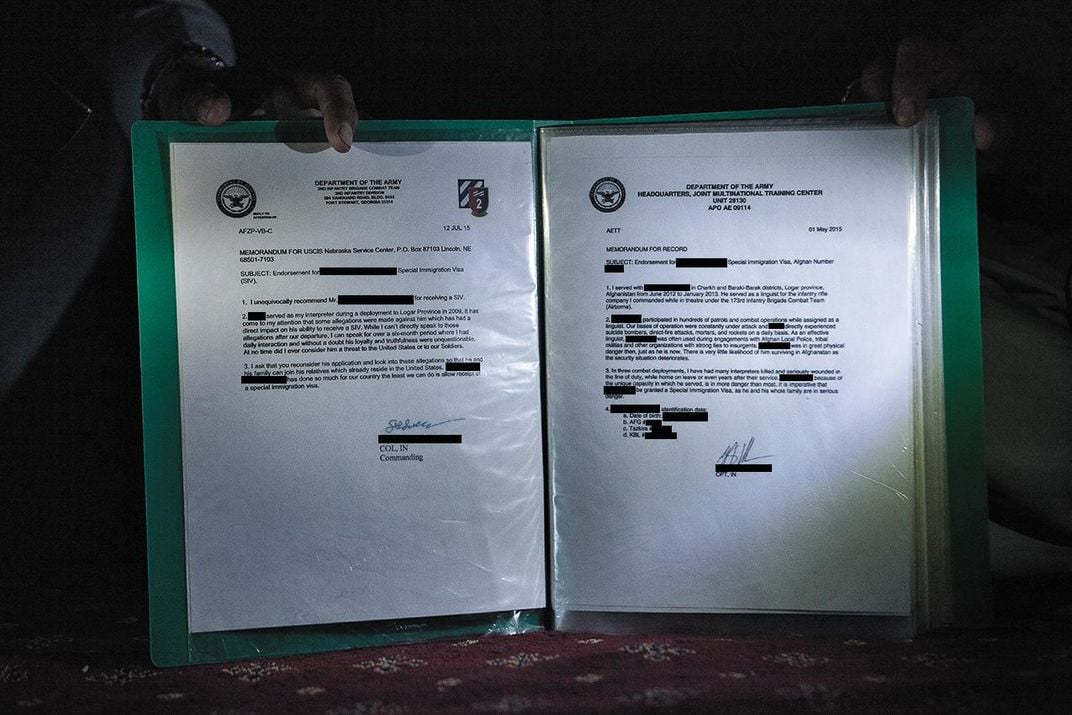

Former soldiers who depended on interpreters say that the military already screened these men and that they passed the most basic test—they were entrusted with the lives of U.S. troops, and at times risked their own. Moreover, the SIV vetting process is rigorous, entailing no fewer than 14 steps. Documentation of service is required. So is a counterintelligence exam, which may include a polygraph. And so is proof that an applicant has come under threat. Supporters of the SIV program argue that some of the requirements are virtually impossible for some interpreters to meet. They’ve been unable to gather references from long-departed supervisors or from defunct contractors. They’ve flunked an SIV polygraph exam despite passing previous polygraphs—a problem that advocates blame on the exam, which isn’t always reliable.

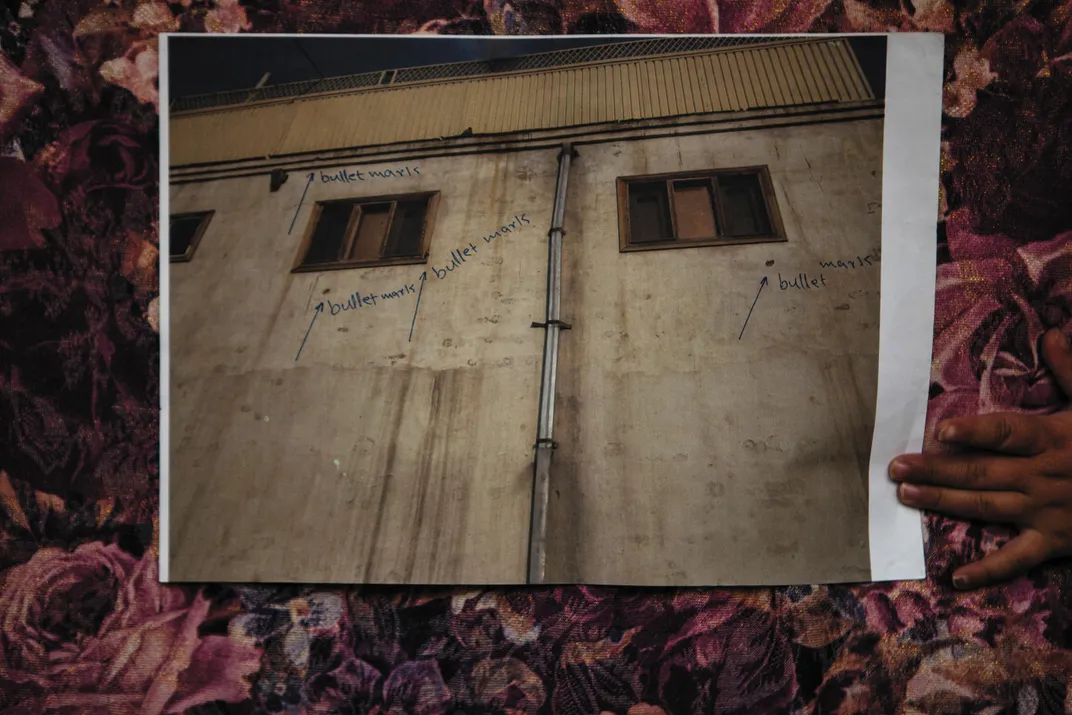

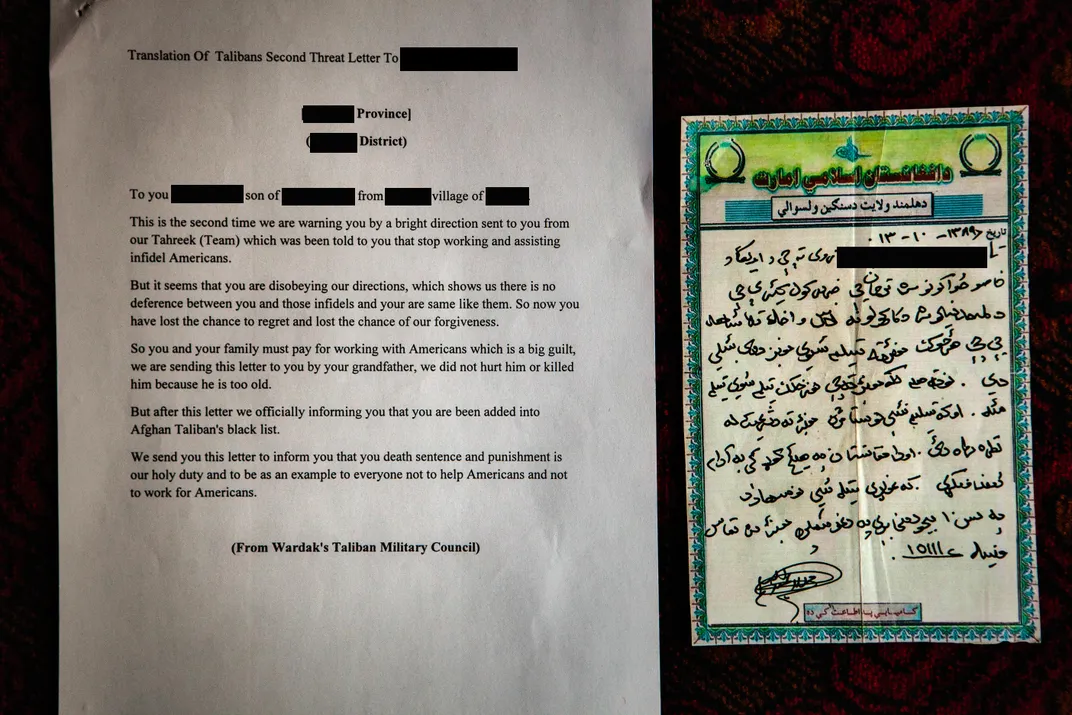

One especially fraught requirement is the need to document danger. This has inspired a new literary genre called the Taliban threat letter, which warns a recipient of dire harm for having aided the enemy. Advocates say the threats are real—delivered on the phone or in person—but that the letters may be concocted for the SIV application. To be sure, Afghan authorities determined that the letter found on Sakhidad Afghan’s corpse was the real thing. But the Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said in a recent telephone interview with Smithsonian that the Taliban does not usually send warning letters. He also said interpreters are “national traitors.”

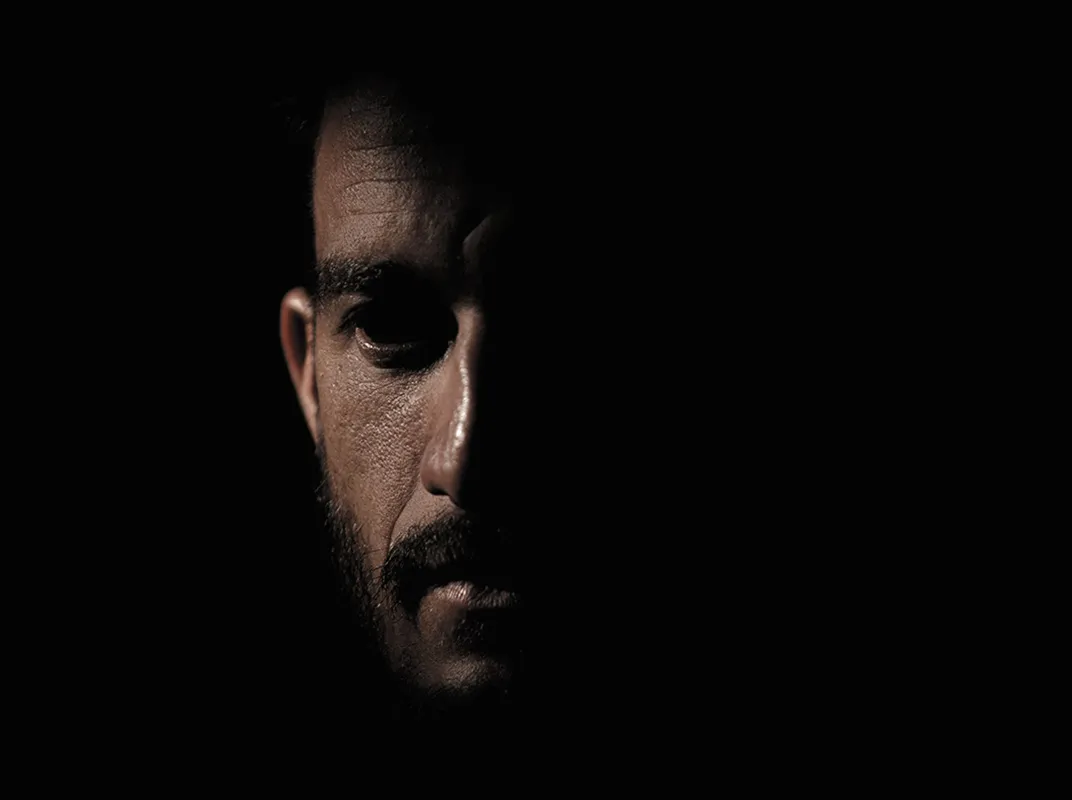

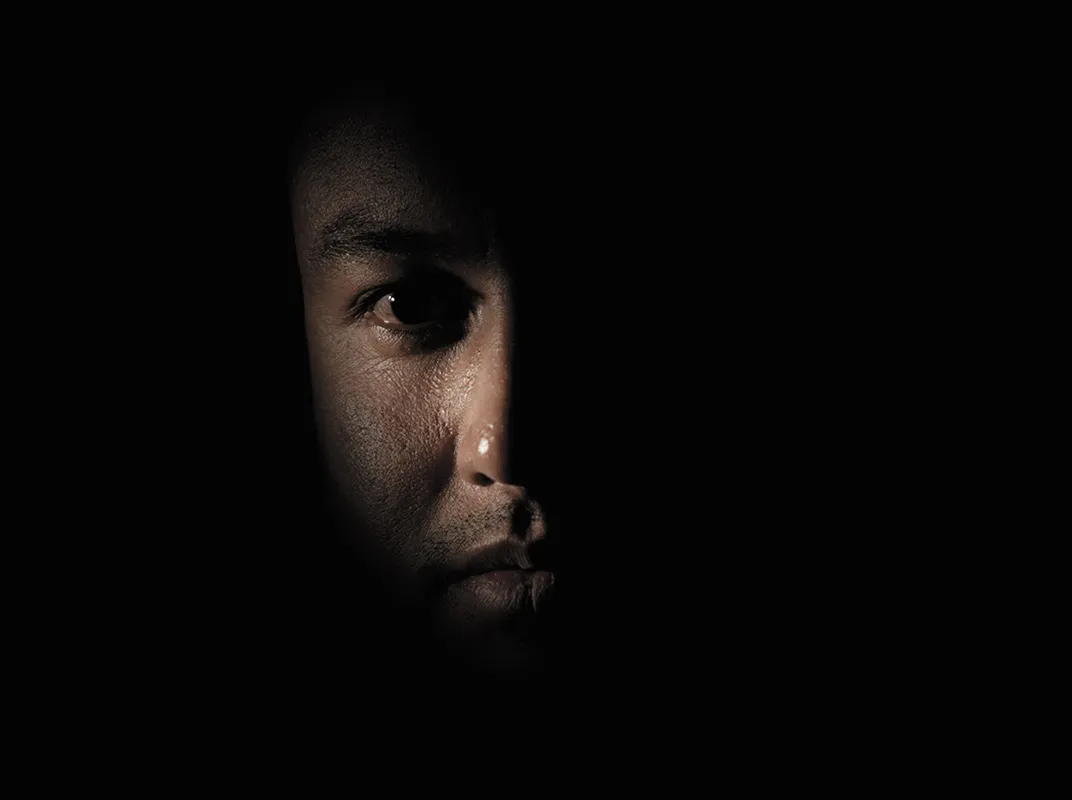

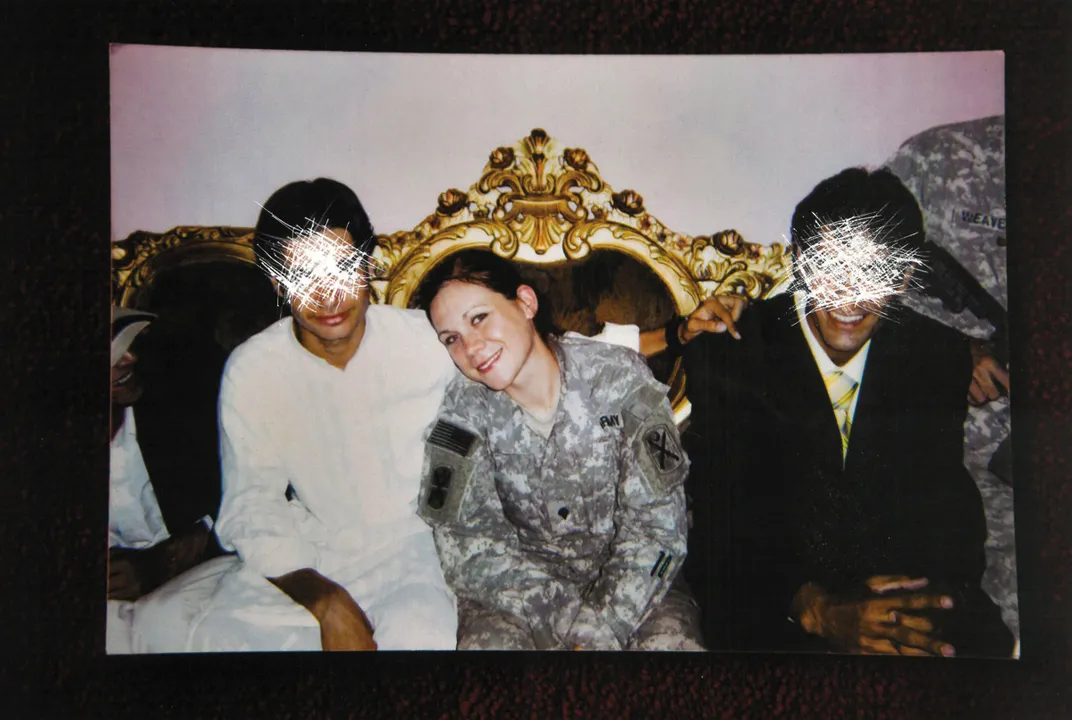

The fate of Afghan interpreters left behind troubles Erin Trieb, an American photojournalist, who covered American infantry units in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2011. On a trip to Kabul last year, Trieb met a man named Mashal, who had been an interpreter for nine years and was now waiting to see whether he would be approved for an SIV. “He said he wouldn’t live with his family, his wife and three daughters, for their own safety,” she says. “He pulled his daughters out of school for the same reason.”

Trieb sought out other former interpreters, to capture the anxious shadow land they inhabit. They asked that she refer to them only by partial names and that her photographs not reveal too much of their faces. “Their service in the U.S. military is this big secret in their lives,” she says. “They can’t tell their friends, they can’t tell their relatives, they don’t even talk about it with one another. They’re always looking over their shoulders.”

As for the brothers of Sakhidad Afghan who were threatened by the Taliban, two fled the country and now live in Indonesia. The third has remained behind. He drives a truck. His mother says he’s now the family’s breadwinner.

Related Reads

Compelled Street Kid

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/44/d744d056-0531-4881-8d65-6c1f2f870006/nov2016_m06_afganinterpreters.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)